‘Longlegs’ Review: A Haunting Tale of Dread and Sorrow

‘Longlegs’ has been hyped endlessly since secret screenings began earlier this year. People have said some wild things about the latest Osgood Perkins horror movie, from panic attack-inducing scenes to being dubbed the literal manifestation of evil. You might think the writer-director had imbued the celluloid with Satanic prayer himself. While it’s not quite as terrifying or disturbing as it’s been made out to be, ‘Longlegs’ is still a damn good film—unnerving, atmospheric, and surprisingly sorrowful.

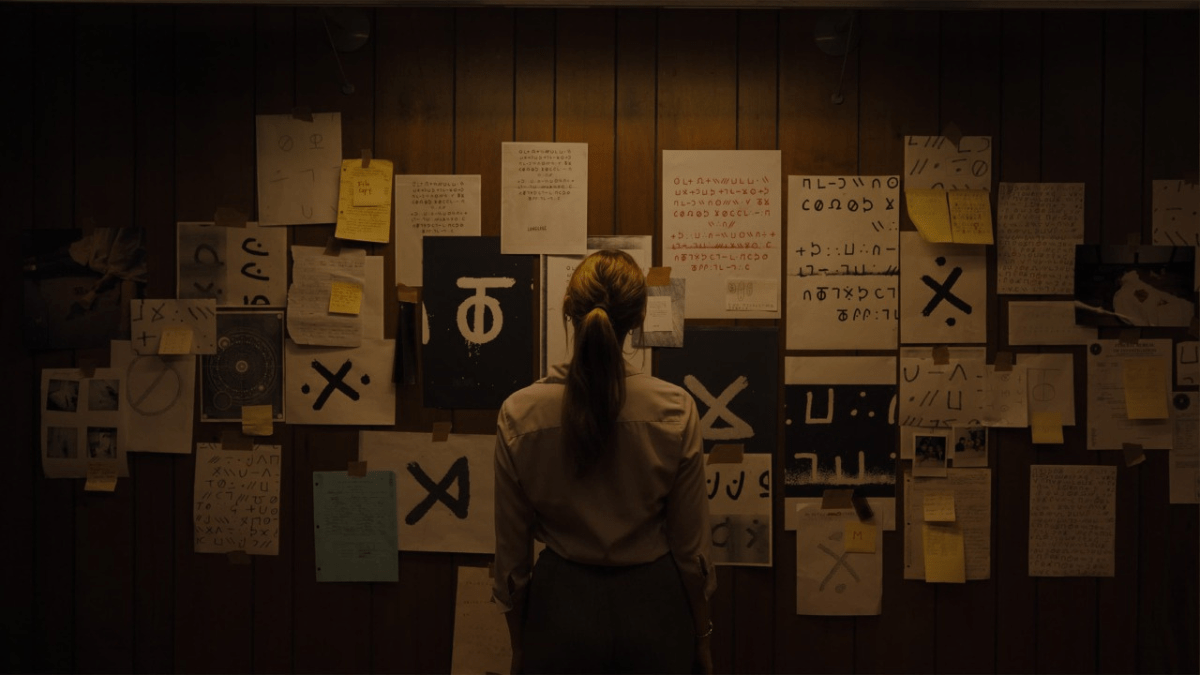

The film starts with a simple premise. FBI Agent Lee Harker (Maika Monroe) is assigned to a case long thought to be ice-cold. Over decades, several families have been found dead in apparent murder-suicides, each crime scene marked by a birthday card signed by “Longlegs.” Harker, who seems to have some sort of psychic ability, begins to dig deep into the case. What she eventually unearths will have repercussions that reach through time.

Also Read: ‘Still Wakes The Deep’ Review: A Decent Horror Game With a Spooky Premise

Perkins masterfully sets up the film, building dread through a quiet opening scene that explodes into a cacophony of terror. From there, things move relatively quickly. Dread mounts as Harker becomes almost deliriously obsessed with connecting the dots between the violent incidents. Nothing phases her—not gruesome crime scenes or cryptic letters with ominous messages. Harker is a bit of a loner; we only see her interact with co-workers, and she’s cautious about how much she shows of herself to them. The first time we see Harker smile, she’s speaking to her mother Ruth (a deliciously menacing Alicia Witt), and it’s clear their relationship is strained.

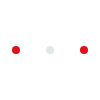

Harker is alone in her quest to hunt down Longlegs, as demonstrated during a particularly chilling scene where she’s visited by someone while poring over evidence at home. It’s one of the most effective sequences of the film. Perkins uses masterful sound design and camerawork to create a sense of unease that sinks into the bones and stays there.

At times, ‘Longlegs’ feels as if it’s pulling some punches. When we finally meet Cage’s demented serial killer, the film’s tone subtly shifts. However, we don’t spend enough time with him to feel truly terrified until it’s too late. Cage’s performance is deranged enough, and Longlegs’ voice won’t be forgotten. The way Perkins deploys brief looks at him leading up to the big reveal raises the tension until it snaps like the crack of a broken bone. Once that tension breaks, ‘Longlegs’ loses a bit of the terror it sustained in its first half. One twist is telegraphed too early, while others fall short due to plot points that feel excised from the script.

Perkins deals heavily in satanic imagery in ‘Longlegs,’ perfect for the era and setting in which it takes place, but that’s all it is. There’s something to be said about mystery and the unknown, especially in a film that uses the unseen as a tool for terror, but leaving too much out feels less like restraint and more like something undercooked.

This doesn’t make Longlegs any less effective, though. Expectations certainly played a role in my initial response to the film, but the more I sat with it, the easier it was to see Perkins’ vision. The marketing for the film is nothing short of brilliant, but it promises something that Longlegs can’t follow through on. It’s not a film pulled from the depths of hell, infused with the kind of violence meant to shock. It’s a slow ride, one that makes us realise that hell isn’t just below us—it can be all around us, in a kindly woman wearing a nun’s habit or a teenage girl recovering from a traumatic incident.

‘Longlegs’ isn’t a horror movie in the traditional sense. It will leave you feeling grimy like you’ve just witnessed something better left in the filing room cabinets filled with case files and crime scene photos. Despite its plot shortcomings, Perkins develops an aesthetic that is slippery and contradictory—the digital clashes with the analogue, the satanic panic of the 70s with the cold, steely practicality of the 90s.

All of this is anchored by Monroe, one of the 21st century’s most underrated scream queens. Harker is a quiet character, not quite shy, just unwilling to open up to people. Using her face alone, Monroe shifts from morbid curiosity to abject terror and emotional devastation, culminating in a killer final shot that encapsulates what’s so unnerving about the movie. Sometimes fear doesn’t immediately register—it can be a seed, planted and cultivated over time. Once a full bloom settles in, it’s hard to shake the fears that grip you.